The Palos Verdes Art Center Hits an Important Milestone and Looks Ahead to an Innovative Future

PVAC at 90.

- CategoryPeople

- Written byGail Phinney

If it seems like the Palos Verdes Art Center has been around forever, that’s because it has. Palos Verdes Community Arts Association was founded in 1931 as the cultural arm of Palos Verdes Estates. Since then, it has played a significant role in the development of the Palos Verdes Peninsula and in the lives of its people.

Malaga Cove Library by Myron Hunt, 1930, Palos Verdes Estates (Palos Verdes Homes Association Photograph Collection, Local History Center, Palos Verdes Library District)

Perhaps your parents and grandparents are longtime members and you grew up taking classes and visiting the galleries on school tours. Or maybe your elementary school children enjoy quality art instruction through Art At Your Fingertips, PVAC’s venerable school-based volunteer outreach program. Throughout its 90-year history, Palos Verdes Art Center has been more than an educational resource to the community; it has been a cultural touchstone to generations of its residents.

The story of the Palos Verdes Art Center begins in the early days of the Peninsula’s development. When Myron Hunt was commissioned to design a public library in 1929, it was determined from the start that the building would include an art gallery. The Committee on Art Exhibits and Art Functions was formed when the Palos Verdes Public Library and Art Gallery opened in 1930, organizing exhibitions and events.

Within a year the committee determined that a nonprofit membership organization should take over responsibility “for the advancement of knowledge and study of painting, sculpture, architecture, landscape architecture, music, drama and the applied arts.” Annual membership dues would begin at $1.

On May 11, 1931, the Palos Verdes Community Arts Association (renamed the Palos Verdes Art Center in 2000) received its state charter. What followed was a series of exhibitions, programs and community events that set a standard of excellence for the next 90 years.

Beginning in the 1930s, Annual Purchase Prize Exhibitions featured the leading painters of the time, garnered the winner a $500 award and gave the center a collection of premiere California plein air paintings. In addition to showcasing local artists, collaborations with regional organizations such as the California Watercolor Society, California Society of Printmakers, California Art Club, Women Painters West and the American Institute of Architects exposed the population to a rich variety of artists, art forms and art-making processes.

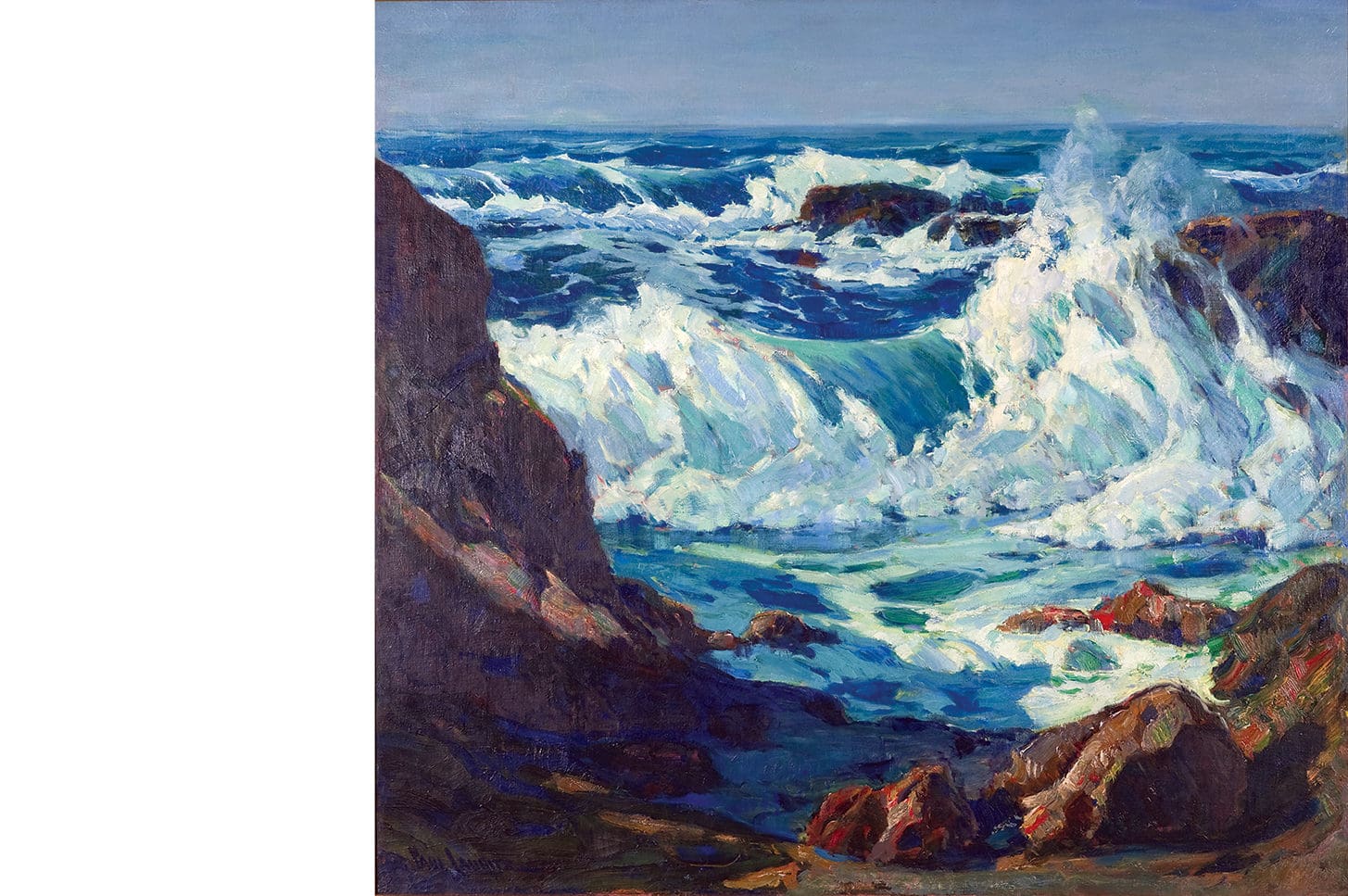

Students from Malaga Cove School view Paul Lauritz’s Western Sea and Coast in the 1931 Second Annual Purchase Prize Exhibition

Enlightening audiences by showcasing art of the moment became an overarching theme of the exhibitions program. Because the Peninsula was geographically isolated and sparsely populated, partnering with well-established cultural institutions enabled exhibitions to continue, even during the difficult WWII years. This was due in part to extraordinarily forward-thinking members like Mildred and Grant Beckstrand.

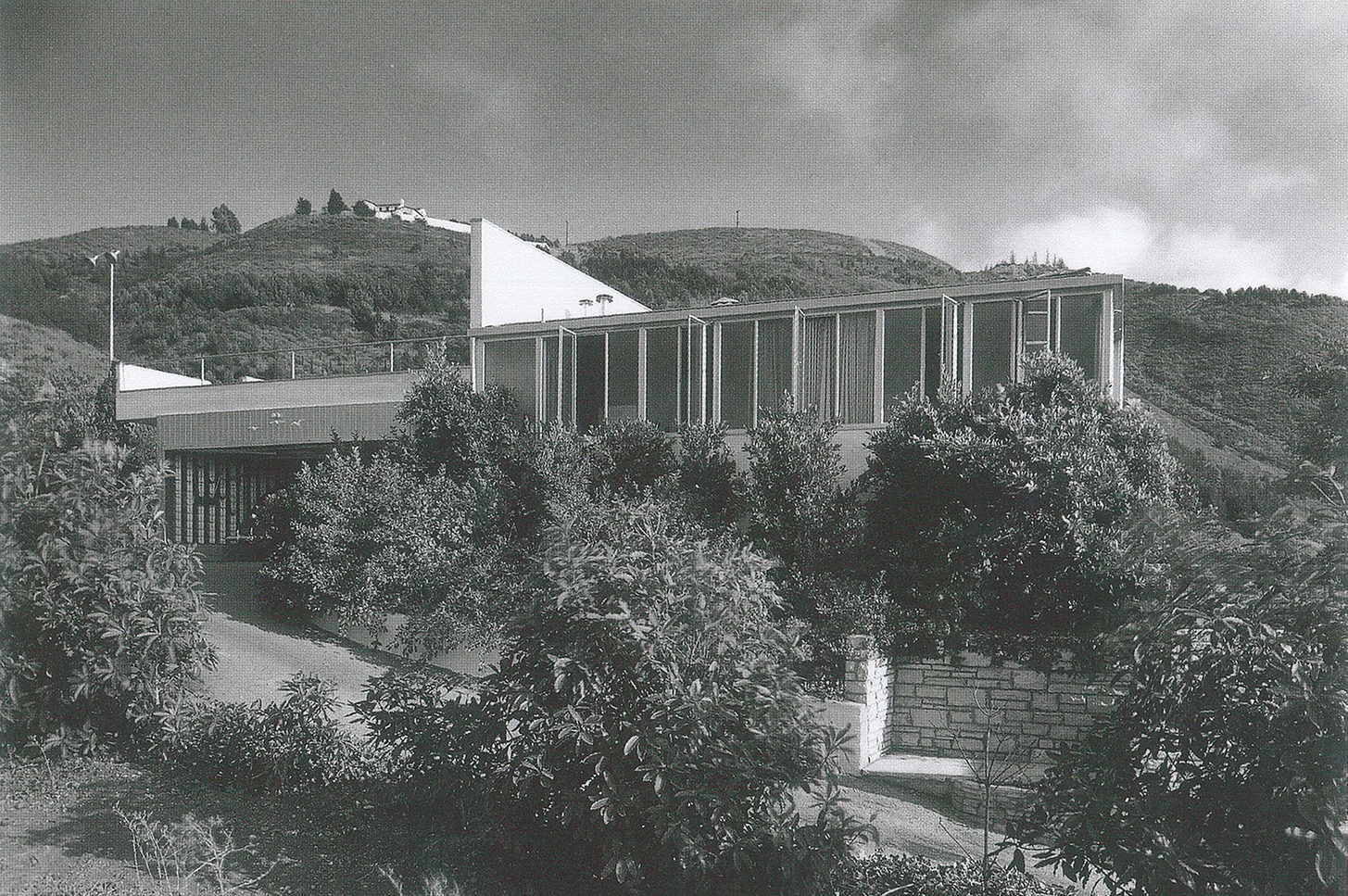

A modern couple in their own right, the Beckstrands commissioned architect Richard Neutra to design their Palos Verdes home, completed in 1940—the same year they joined PVCAA. The glass and steel design was a direct departure from the accepted Spanish Revival style and well ahead of its time.

Mildred, who had a brother in the New York art world, arranged for the 1941 exhibition 20th Century Paintings from the Museum of Modern Art, NY. It cost $60 to travel and mount the exhibition.

“We had to make our own entertainment,” she said, “because there was very little art in Los Angeles.” Mildred became the first female president of the association in 1949 and continued to be an active member for nearly 50 years.

Another extraordinary member who made a lasting contribution to the art center was film enthusiast Curt Wagner. In 1956 Wagner founded the Film Society, with screenings held at The Strand Theater in Redondo Beach. These events often included local Hollywood luminaries. Hermosa Beach resident and silent screen actress Mae Marsh was present at the screening of her 1916 film Intolerance, directed by D.W. Griffith.

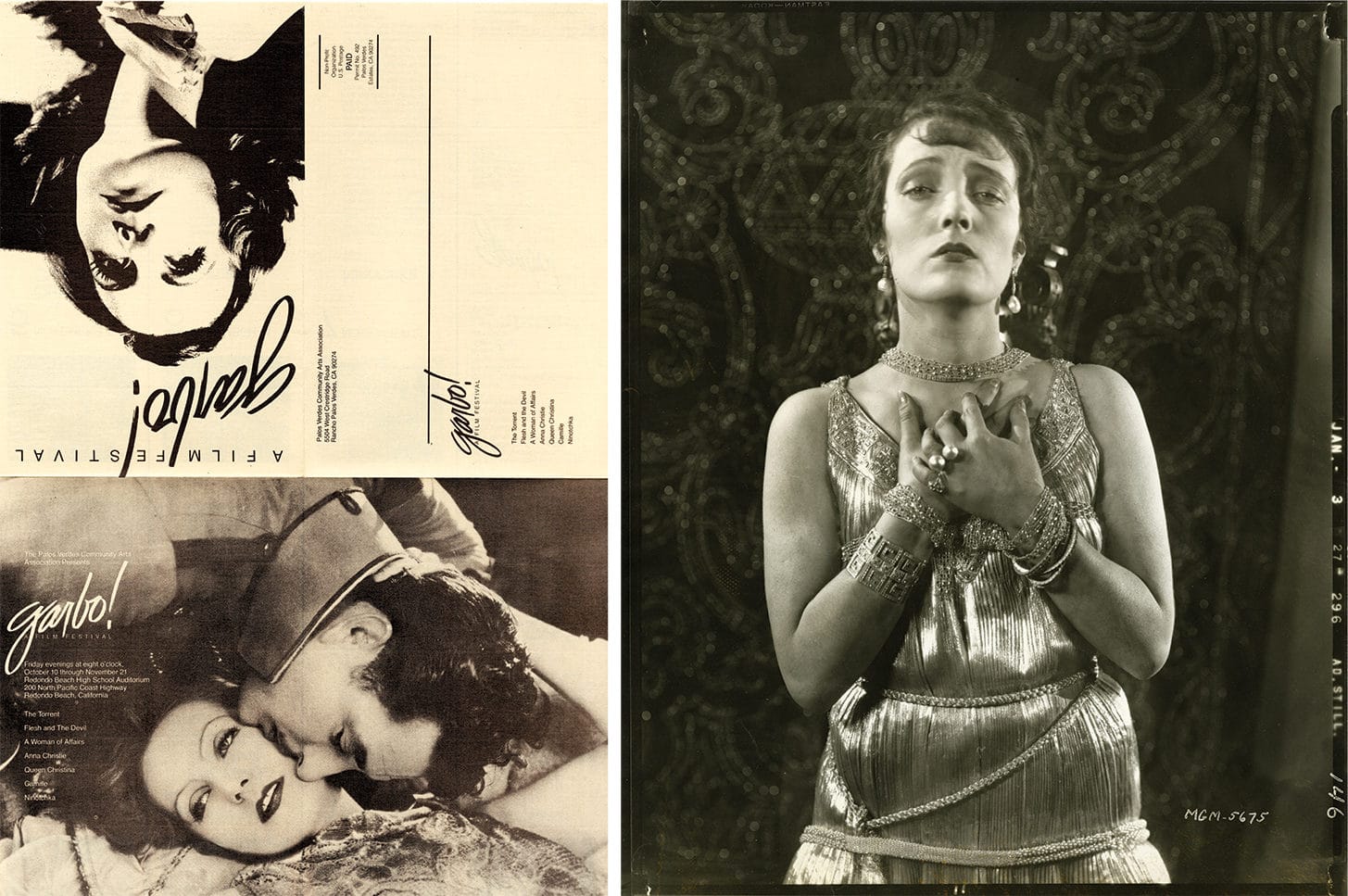

In 1980 Wagner purchased a collection of early Hollywood ephemera from collector Paul Ballard for $50,000, expressly for donation to the center. Along with an impressive array of rare art books and art and architecture color slides, it included 18,000 black-and-white slides of movie stills taken by set photographers of rising stars, as well as Hollywood giants Greta Garbo, Rudolph Valentino, Clark Gable and Marlene Dietrich. The collection documented the film industry from its silent years in 1912 through the WWII years and included rare vintage films dating from 1909 to 1921.

Dr. Grant Beckstrand House by Richard Neutra, 1940, Palos Verdes Estates

In addition to being a valuable resource for the art center and the community at large, it launched a successful Garbo Film Festival and became the catalyst for an ongoing film series and lecture program hosted by Wagner and USC film school graduate Frank Brown throughout the 1980s. PVAC donated the Ballard Collection to the USC School of Cinematic Arts in 2013.

The postwar era brought growth and change to the Peninsula and, by extension, to the Palos Verdes Art Center. Attracted by the scenic landscape, clean air, ocean views and proximity to Hughes Aircraft Company and Northrop Corporation, the Palos Verdes Peninsula became a desirable destination. Between 1950 and 1970, the population of Palos Verdes Estates grew from 2,000 to 13,300. The Palos Verdes Art Center was woven into the fabric of the mid-century modern community with the opening of the Lowell Lusk-designed building in 1974.

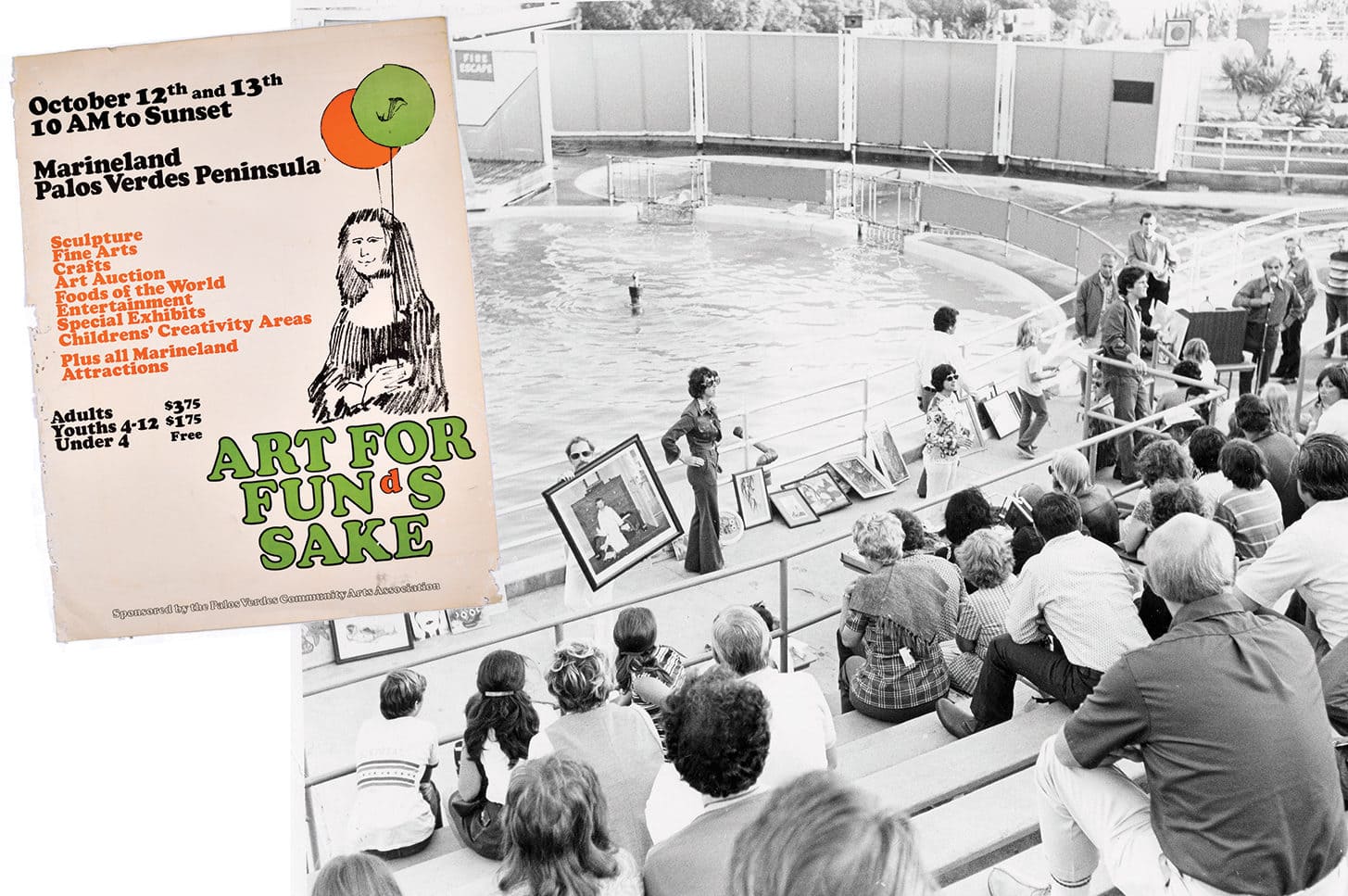

The purchase of the land for the building was largely made possible by Art for Fun(d)s Sake—a two-day, family-friendly, outdoor community extravaganza run by an army of volunteers. It was a much-anticipated annual event combining art, entertainment and food. Started in 1963, it was a major fundraising source for the center and continued for the next 40 years.

It reached its heyday in the ’70s when it was held at the 32-acre Northrop Research Park. It was moved to Marineland in the mid-’70s, where attendance peaked at 40,000 in 1974. The total profits of $34,000 went to the building fund.

Artists and craftspeople were drawn from arts communities up the coast as far as Northern California, with an emphasis on introducing the public to a new range of styles and materials—often providing a showcase for young, up-and-coming talent. In 1972 Los Angeles architect Frank O. Gehry displayed his innovative laminated cross-section cardboard in the sculpture garden. Gehry’s cardboard furniture was later featured in the 1989 PVAC exhibition,The Corrugated Show.

Promo for Garbo Film Festival and silent still from Ballard Collection

As the Peninsula grew, Palos Verdes Art Center expanded to meet the demands of the community. Classes, which were previously held at satellite locations throughout the South Bay, were now consolidated under one roof. PVAC quickly established itself as a leader in the field of art education. One discipline in particular—ceramics—was experiencing a Southern California revival and flourished at the new location. It remains one of the most popular departments to this day.

Many new members were introduced to PVAC through the school. One new member, Jan Napolitan, had a practical reason for taking a ceramics class in the early ’70s: She had broken a cherished serving dish and wanted to learn to craft another. Then, in her words, she “got stuck there.”

Nearly 50 years later she’s still there, embodying the spirit of volunteerism that sustains the organization. She has held virtually every position on every committee and currently serves on the board of trustees. Jan observes, “The love that people have for the institution makes it what it is.”

Now a beloved ceramics instructor, Jan believes that PVAC developed a reputation for having the best ceramics department outside the university system because it drew from the university system. Influential ceramicist Adrian Saxe led the department before going on to an illustrious teaching career at UCLA.

“We then were able to get our ceramics instructors from mainly UCLA at Adrian’s recommendation,” Jan says. “We had so many opportunities to learn from some really great people.” This included workshops that introduced students to diverse, multicultural aesthetics from visiting artists.

1973 Art for Fun(d)s Sake at Marineland

Outstanding exhibitions showcasing important California leaders in the field of ceramics followed, foregrounding new techniques and processes. In 2008 PVAC presented Influences, a survey of contemporary Southern California ceramics that celebrated the many artists who shaped the art center’s ceramics department and went on to great acclaim, including Ralph Bacerra, Lukman Glasow, Richard McColl, Harrison McIntosh, Neil Moss and Peter Shire. The show was co-curated by Jan Napolitan, Jackee Marks and exhibitions director Scott Canty.

Beginning in 1998 and throughout his 15-year tenure as exhibitions director, Canty was instrumental in bringing the L.A. art scene to Palos Verdes. As curator at the L.A. Municipal Art Gallery in Barnsdall Art Park, he had access to an extensive registry of artists and developed working relationships with notables Larry Bell, Charles Arnoldi and Lita Albuquerque—all of whom exhibited and lectured at the art center in the early 2000s.

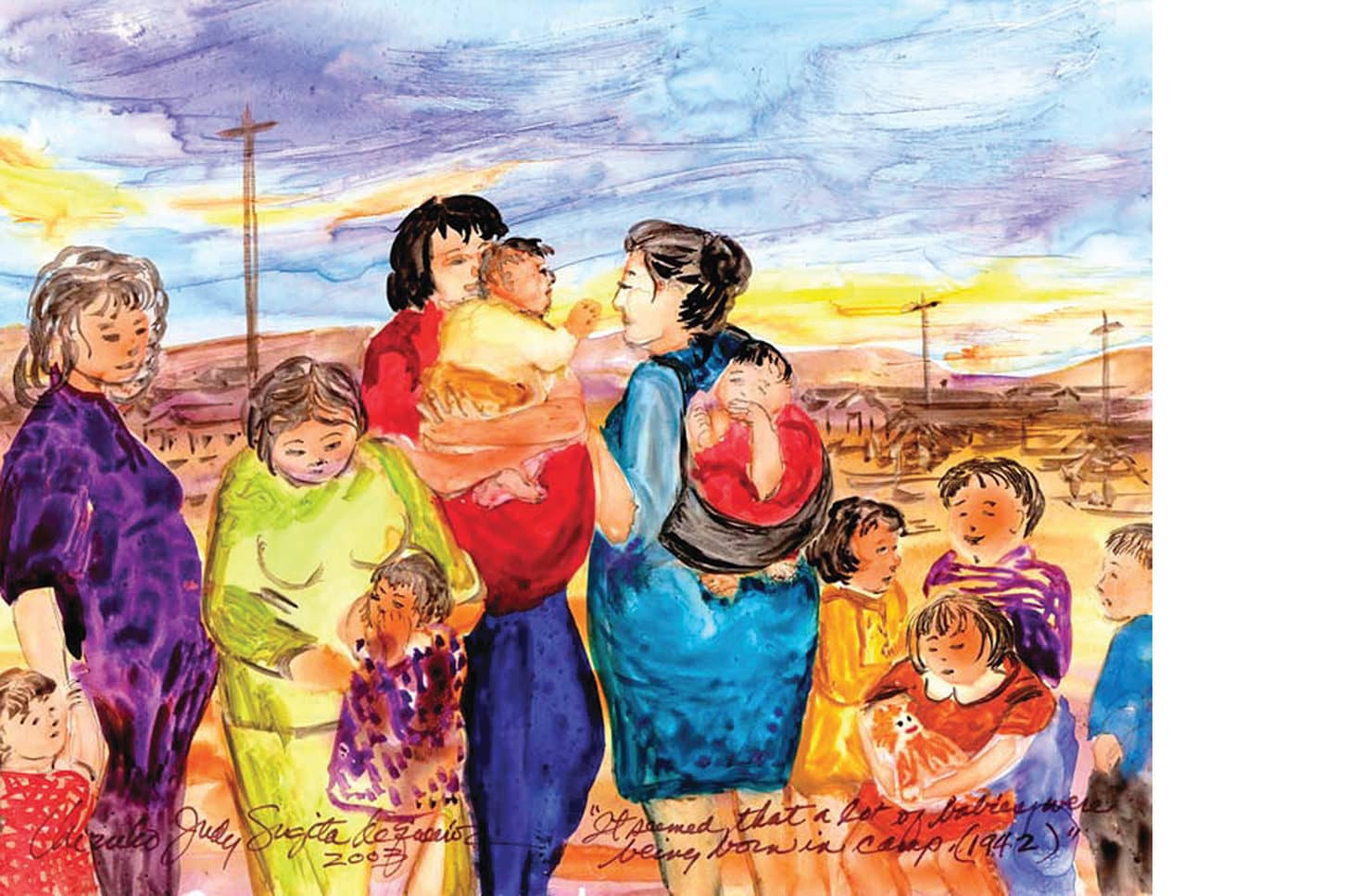

However, one of Canty’s fondest memories was working with a former art teacher and department chair in the Palos Verdes Peninsula Unified School District. Exhibited in 2009, Camp Days: 1942-1945 presented a series of watercolors by Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz, narrating her years as a child interned at a camp in Poston, Arizona. The exhibition resonated deeply with the South Bay Japanese American community, and Canty recalls a moving encounter in the gallery.

Chizuko Judy Sugita de Queiroz, It seemed like a lot of babies were being born in the camp (1942), 2003, Giclee Print

“Two Japanese men came up to me and said how thankful they were that we had this exhibition,” Canty shares. “The last time they saw each other was at Manzanar as children. They recognized each other in the exhibition, and they broke down crying. It was her exhibition that brought them back together; it was such a beautiful experience.”

As community involvement continued to grow, it became apparent that the old facility could no longer meet the needs of the institution in the new millennium. In 2000 the International Architecture Competition solicited ideas for the renovation and expansion of the Palos Verdes Art Center; 652 teams (many consisting of university students) from 37 states and 44 countries on five continents participated. The online forum was a first for the center. Although the winning design by Italian architect Andrea Ponsi was never executed, the competition culminated in an exhibition of the outstanding entries.

After a series of minor upgrades, the Lowell Lusk building ultimately underwent a major renovation. It was renamed the Palos Verdes Art Center/Beverly G. Alpay Center for Arts Education and reopened in 2013 with the comprehensive exhibition Then and Now: One Hundred Years of California Impressionism—a collaboration with the California Art Club.

Harkening back to PVAC’s roots, the exhibition included the historical work Western Sea and Coast (Crashing Harmony) by Paul Lauritz. This piece had been the winning entry in the 1931 Second Annual Purchase Prize Exhibition of Paintings.

Beginning in 2013, executive director and curator Joe Baker entered the scene and made his mark on the building by transforming it into a large-scale public art project. First he wrapped it with the iconic celebrity portraits of photographer Douglas Kirkland, followed by the neobaroque floral design of Portland, Oregon artist Deb Stoner, whose work was selected from nearly 200 international entries.

Paul Lauritz, Western Sea and Coast (Crashing Harmony), 1930, oil on canvas

Baker, a mid-century modern enthusiast, also put his spin on the already popular Palos Verdes Dream House Raffle by including a number of architecturally significant homes. Accompanying exhibitions shed important light on architects John Elgin Woolf, Pierre Koenig, Aaron G. Green and the firm Ladd & Kelsey.

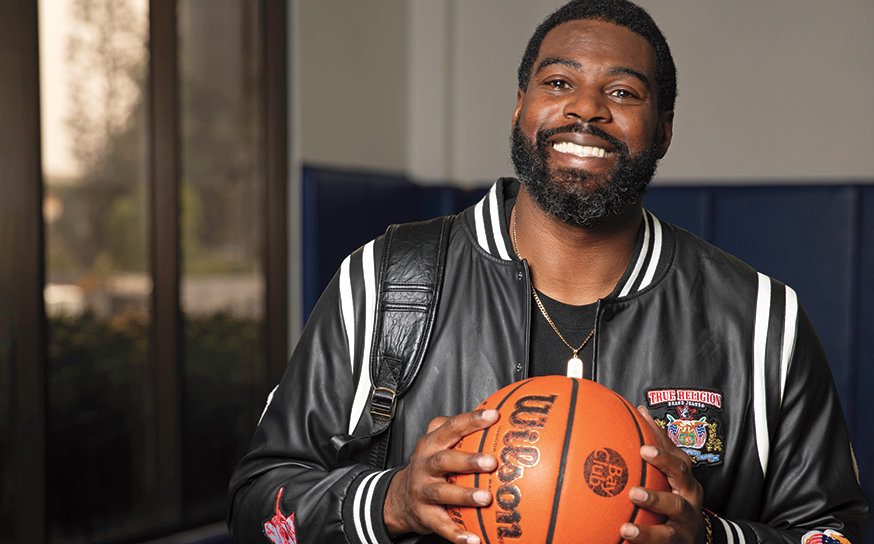

PVAC’s newest exhibitions curator, Aaron Sheppard, is no stranger to the organization, having served as chief preparator for seven years before assuming his new position in March 2020. Shortly thereafter, the art center was closed in compliance with state-mandated COVID-19 restrictions, but the work of bringing art to the community continued. Sheppard observes, “It’s the same players, but with COVID-19 the game has changed and we had to reinvent ourselves using technology. It’s been a learning curve.”

The learning curve not only involved developing new methods to present content; it also involved determining what content to present in a rapidly changing climate. PVAC’s response was the exhibition Skin in the Game, curated by Brent Holmes. It presented works by 17 artists that challenged mainstream assumptions of Black identity and artistic practice.

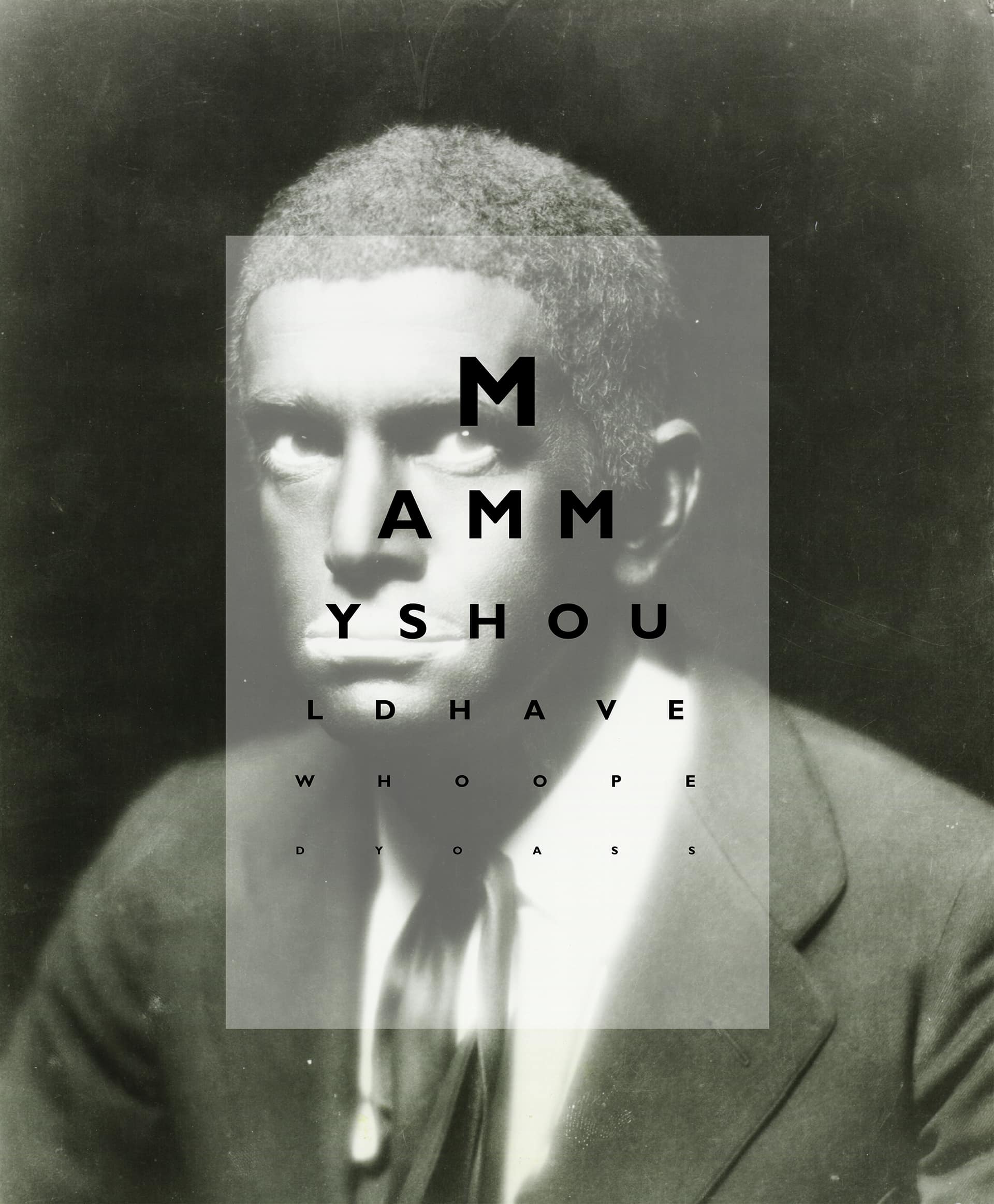

The accompanying series of video talks moderated by Holmes enabled an expanded audience to better understand the artists and their work. Included in the roster of artists was former Municipal Art Gallery director Mark Steven Greenfield. He had curated the 2006 PVAC exhibition Bling, which showcased emerging Black artists like Sadie Barnett—still an art student at the time—who has since gone on to national prominence.

Mark Steven Greenfield, Problem Child, 2001, Inkjet Print

Supporting and showcasing student artists has become a PVAC tradition. Since 2014, thanks to the generous support of Dr. O. Allen Alpay in memory of his wife, Beverly G. Alpay, PVAC’s Alpay Scholarship University Student Juried Exhibition: Now Trending has provided an annual showcase and scholarships that have enabled these students to pursue their passion. So when COVID-19 restrictions preempted the 2020 exhibition, the art center responded with Still Trending, a “where are they now?” online exhibition revisiting six talented artists who won Alpay scholarships or received honorable mention in the past.

The transition from engaging the public in the physical space to the presentation of online exhibitions, programs and classes would not have been possible without the commitment of the board of trustees and the leadership of executive director Daniela Saxa-Kaneko. While other arts nonprofits suffered debilitating cutbacks or shuttered completely, Palos Verdes Art Center entered its 90th year without interruption—having evolved creatively during this period of innovation thanks to a small but dedicated staff.

What lies ahead? A celebration of the Palos Verdes Art Center’s 90th anniversary is scheduled for 2021, with a series of virtual exhibitions that look back at its history while continuing to showcase the best and brightest in contemporary art. Although a highly anticipated reopening celebration is the ultimate goal, due to uncertainty about the pandemic that date has yet to be determined at the time of this writing.

But Sheppard remains optimistic. He asserts, “Because we opened the interwebs, when we do open the doors, I think it’s going to be a much more inviting place. This has made us better people, better at our jobs, more sensitive, more caring.”

And so, the story continues …

Learn more about this year’s anniversary programming at pvartcenter.org/pvac-90.