Remembering the Ishibashi family’s agricultural legacy in Palos Verdes

Who visited Annie’s Stand for fresh fruit?

- CategoryEat & Drink, People

- Written byChris Ridges

- Photos Courtesy ofCSU Dominguez Hills Archives

It may take more than a little imagination to realize that, at one time, the Palos Verdes Peninsula was an agricultural oasis. Its transformation from desert to harvest-land began in 1882 when the 16,000-acre Bixby Cattle Ranch (essentially the entire Peninsula) began leasing specific areas to farmers. For $10 per acre annually, ambitious farmers could begin improving the soil and establishing their crops.

Nearby Torrance, Carson and Gardena were partially farming communities too, specializing in flowers and berries. Palos Verdes was prime for so-called “dryland” farming—an expensive and risky method suited for the area’s particular climate and weather.

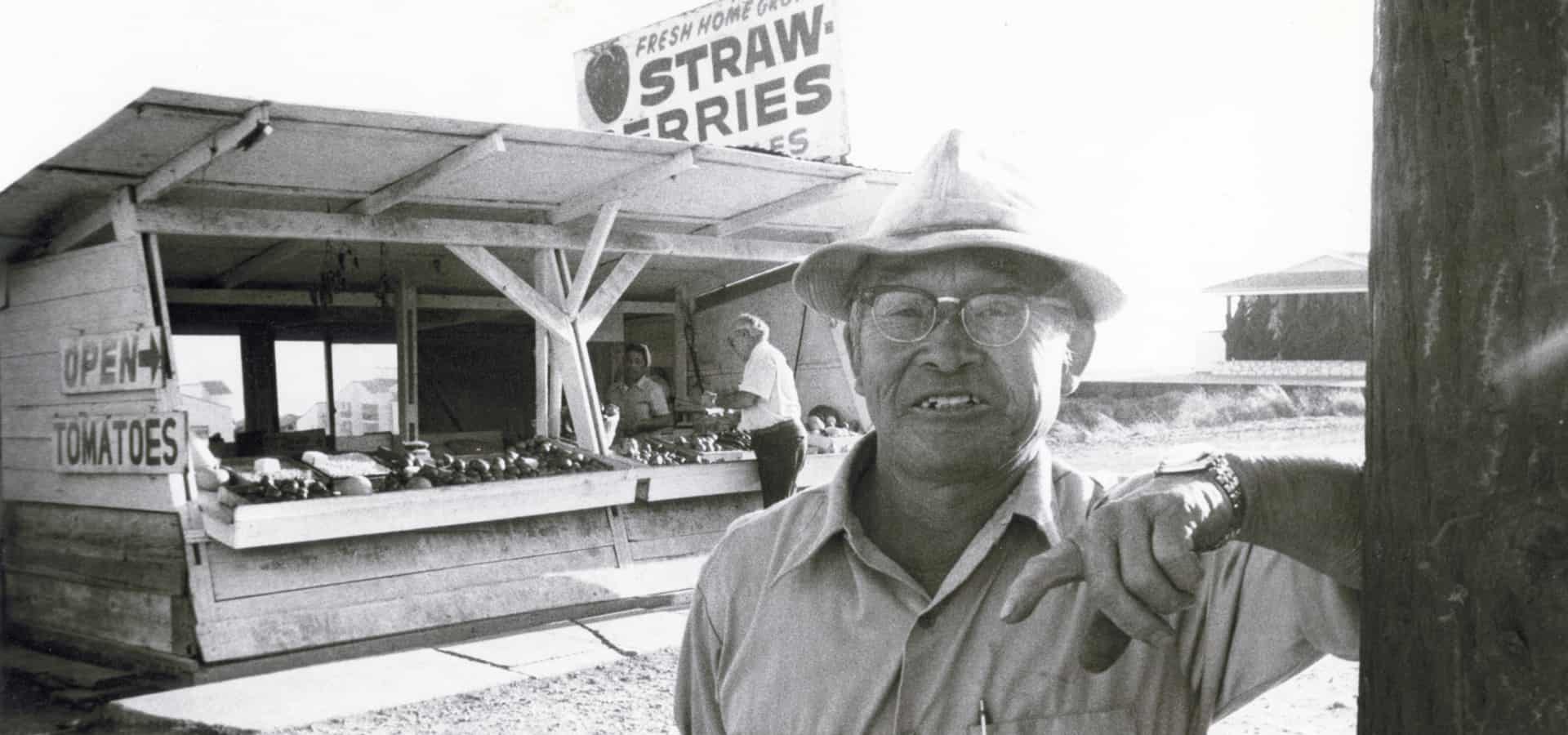

One of the most successful and significant families to take advantage of the Bixby offer was the Ishibashis, a family from Okayama, Japan. Arriving in the U.S. in 1910, the Japanese American family began reimagining their 5-acre Portuguese Bend parcel (adjacent to today’s Trump National Golf Club) into a bountiful farming business. Annie’s Stand, a roadside favorite for decades that was situated next to the farm, offered travelers fresh fruit and a view of their beautifully developed farmland.

The Ishibashis, including founding family members James “Kat” and his wife, Annie, began what would become a long-lasting relationship with the area, its community and its culture. Their children, Richard and Yvonne, continued and expanded the family organization for nearly a century with additional locations established throughout the Peninsula.

Richard and his wife, Sande, were instrumental in maintaining his parents’ vision of bringing visual beauty and prosperity to the areas they farmed. Thought was given to how the rows of different crops would look after planting—arranged and expanded across the gently hilled coastline. Their creative and mindful approach resulted in a natural beauty long shared by locals and tourists alike.

“Firing rifles and pistols in the open fields—a traditional pastime for some residents—would endanger the lives of tractor drivers and other fieldworkers until local police enforcement proved effective.”

Sent to internment camps during World War II, the Ishibashis were among a very few that chose to return. Their family, forced to splinter in different directions, had begun new lives.

Fortunately they began to reassemble. The postwar readjustment was understandably difficult, but they were determined to gather and forge on. Their family was, and is, a model illustration of how Japanese Americans could reenter society to share the new American dream.

In 1949 Richard leased 150 acres near the Torrance Airport and included another much-welcomed roadside stand beside it, featuring the most delicious strawberries in California—sold to motorists by the crate. The attractively cultivated berry rows were visible from Crenshaw Boulevard for decades.

An additional farm was started by Kay and Katherine Ishibashi in Walteria and could be seen from PCH. The family employed hundreds of workers each year in all of its locations and operations.

Among the flowers the Ishibashis excelled in growing were poppies, snapdragons and pansies. Their gorgeous gladiolas were cut two days before blooming and air-shipped to New York City, where they commanded extravagant prices. During the height of their geranium production in the 1950s and 1960s, more than 200 million of the flowers were shipped to the East Coast every year.

Their produce included avocados, tomatoes, carrots, beets, sweet peas, bell peppers and barley. The avocado groves they designed so magnificently in Portuguese Bend became legend. Crates of their tomatoes were trucked daily to San Pedro for shipment to San Francisco’s best restaurants and markets.

But what about those strawberries? The Ishibashis used several varieties of university-type strawberries that would grow abundantly in the PV Peninsula’s mini-clime, March-to-September berry season. The plants were replaced annually to ensure taste, firmness and gargantuan size (their “stem” variety were as big as lemons). The soil was fumigated every year as another painstaking preparation before planting.

The strawberries were sold to the wholesale market and distributed across the country at great demand. For years and years tourists from all over the country as well as fortunate locals could pull over and stop for a crate.

As the Peninsula transformed from farmland into populated communities, new problems arose for the Ishibashis to overcome. When the coyotes disappeared, the realities of civilization set in. In the 1960s motorcyclists, off-road Jeeps and horse trails began to cut through their farm’s multiple rows of fragile, vulnerable produce and flowers.

Vandalism and mischief resulted in upwards of a 10% loss of crops. The property lines were chained off, but the determined, thrill-seeking locals still got through to have their fun and leave their destructive trail. Their vehicles would not only destroy delicate crops but also leave deep ruts in the soil, requiring labor-intensive repair.

Firing rifles and pistols in the open fields—a traditional pastime for some residents—would endanger the lives of tractor drivers and other fieldworkers until local police enforcement proved effective. Local kids would break into the stands during the night and help themselves to cartons of eggs, tomatoes and berries. Thieves would break into their storage sheds and steal hundreds (thousands today) of dollars worth of tools and rifles. As if the jackrabbits, peacocks and pigeons helping themselves to everything in sight weren’t bad enough.

The crops were vanishing from era to era too. A new Palos Verdes Estates home development in the 1950s resulted in the Ishibashis’ famed garbanzo bean export business (mainly for Cuba and Puerto Rico) coming to a complete and sudden end. New terra-cotta tile-roofed homes and paved streets replaced the once flourishing, expansive chickpea fields.

Continued harsh regulations during the 1990s made family farming more and more difficult, as did competition from the local grocery chains. After losing several family members, the Ishibashis closed shop in 2005. Plans to re-open were considered and various efforts were attempted, but none had lasting results. The family held its closing sale in March 2012.

The Portuguese Bend home the family built in 1952, with its incredible view of the ocean and avocado groves, remains the telling reminder of a wonderful era passed.

Holiday Wish List 2025

Our annual holiday gift guide highlights the latest trends in fashion, jewelry and home goods available at local retailers for all of your gifting needs. Don’t let the season’s best and brightest pass you by!

Southbay Restaurant Guide

The holidays are here! Whether you want the perfect spot to take family and friends or a great location to host your festive event, here are some South Bay dining suggestions that combine fabulous food and top-notch service with a warm, welcoming vibe.