A New Exhibit at Palos Verdes Art Center Reflects on the Modern Artistic Evolution of an Ancient Craft

Heart of glass.

- CategoryArts

- Written byGail Phinney

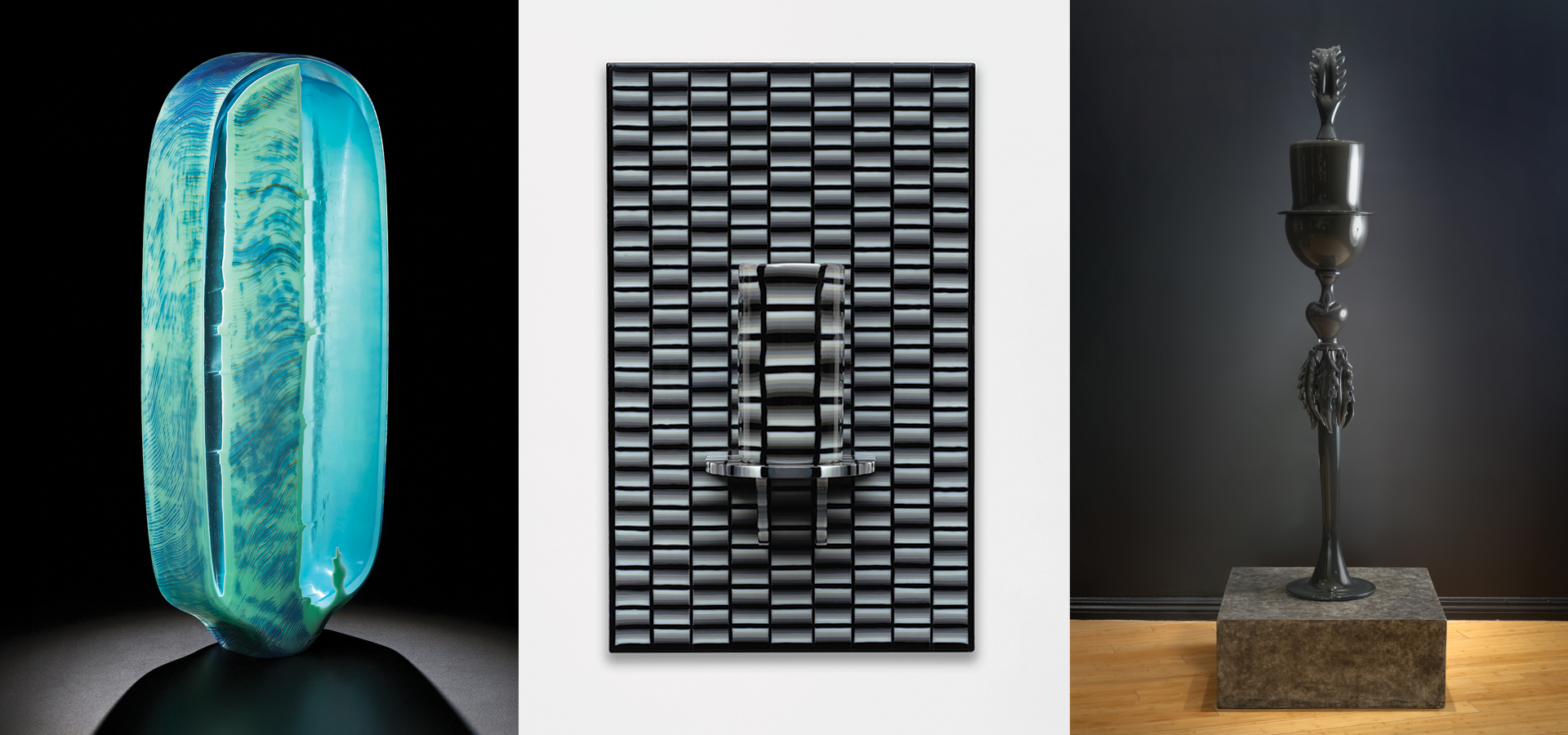

- Ethan Stern, Lunar Light Beach, 2015 (left). Adam Gregory Cohen, Grey Distortion, 2023 (center). Kazuki Takizawa, Guardian II Tux, 2019 (right).

Above

The history of glass, as something purely functional, dates back to ancient Mesopotamia. The first glass was made by heating and fusing sand, soda and lime. Glassmaking spread across the globe to various regions in possession of the natural resources necessary to manufacture glass products that became part of everyday life.

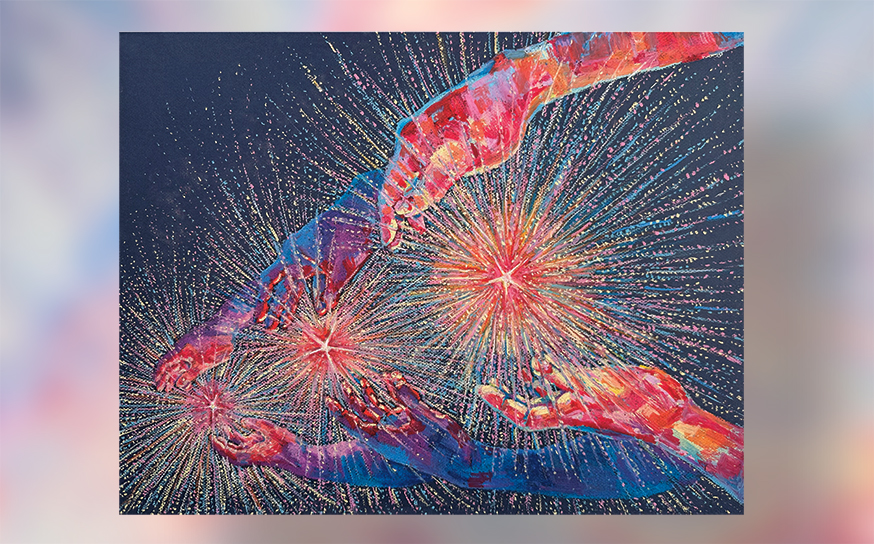

Amanda McDonald Stern, Modular Form 10, 2023

It wasn’t until the 1960s, with the American invention of the small furnace, that a new movement of glass production outside the glass factory took hold in the United States. According to Emily Zaiden, director of the Craft in America Center, “The history of artists making glass objects that are intended for sculptural or artistic purposes—things that are not intended to be used in ways that we traditionally perceive them—goes back to the mid-20th century when individual artists in certain parts of the country started to experiment with ways to work with glass in a studio setting.”

Southern California became a nucleus for some of these artists. The rebellion and freedom of the 1960s and ’70s counterculture movement paved the way for innovation. Craft skills were disseminated through a number of school programs that helped expand the awareness and possibilities for what artists could do with glass and made Southern California a center for art glass.

Curated by Zaiden, The Optics of Now: SoCal Glass at Palos Verdes Art Center showcases approximately 40 works by 20 Southern California artists working in the field of glass. With so many outstanding artists to choose from, Zaiden’s selection presents the viewer with a fascinating glimpse into the innovative artists working in the region and their wide-ranging techniques and approaches to the medium—reflecting the scope and nature of Southern California glass today.

It is not surprising then that several artists in the exhibition are educators, like John Gilbert Luebtow, who instructed and chaired the art department at Harvard-Westlake School in Los Angeles for over 40 years. On view are models of his public art commissions where the artist works in massive scale and across media, including steel and ceramics.

Above | Paul Brayton, Up from the Deep, 2021 (large image). Mariah Armstrong Conner, Tidings of the Lost, 2018 (white glass image). Mariah Armstrong Conner, Tipping Point Project, 2018–2023.

•••

Also featured is one of Luebtow’s former students, Stephen Dee Edwards, who has returned to California after building the hot glass program at Alfred University (New York) to make cast-glass figures infused with irony and wit. Nicole Stahl, who currently teaches 3D art at Harvard-Westlake, contributes a sensual ceramic and cast glass organic sculpture from her Transplants series.

Stahl’s alma mater, California State University, San Bernardino, is home to another exhibiting artist and longtime professor, Katherine Gray, who trained several of the artists participating in the show. Gray’s Illuminating Frequencies illustrates her scientific interest in the chemistry of glass and the processes of bending light.

Gray was a mentor to local glassblower Paul Brayton, a vessel maker who finds his satisfaction in the simplicity of form and the way it transmits light. An instructor at Palos Verdes Peninsula High School, Palos Verdes High School and the Studio School at Palos Verdes Art Center, Brayton was responsible for establishing glass programs at all three locations.

Kazuki Takizawa, Ruby Stripe, 2022

Hiromi Takizawa, an influential glass educator at Cal State Fullerton, has also mentored a number of the exhibiting artists. A native of Japan, she incorporates natural motifs in her fused glass installation Trail Gazing to convey a nostalgic sense of place.

Outside the school programs are pockets of artists, some of whom are interconnected and some who work at independent glass studios scattered around the region. Zaiden believes, “What makes this regional group of glass artists distinct is the sense that they are absorbing what has happened in the world into their material and translating it into their artwork. They are on the pulse of what is happening, and many of them see the metaphorical aspects of glass.”

Kazuki Takizawa uses his art to advocate for mental illness awareness, his glass Guardian series exhibiting the tension inherent in being both strong and fragile. Mariah Armstrong Conner explores environmental issues with her Tipping Point Project, referencing and updating the Roman funerary urn by filling hers with plastic trash collected along the California coast and questioning what we hold as important.

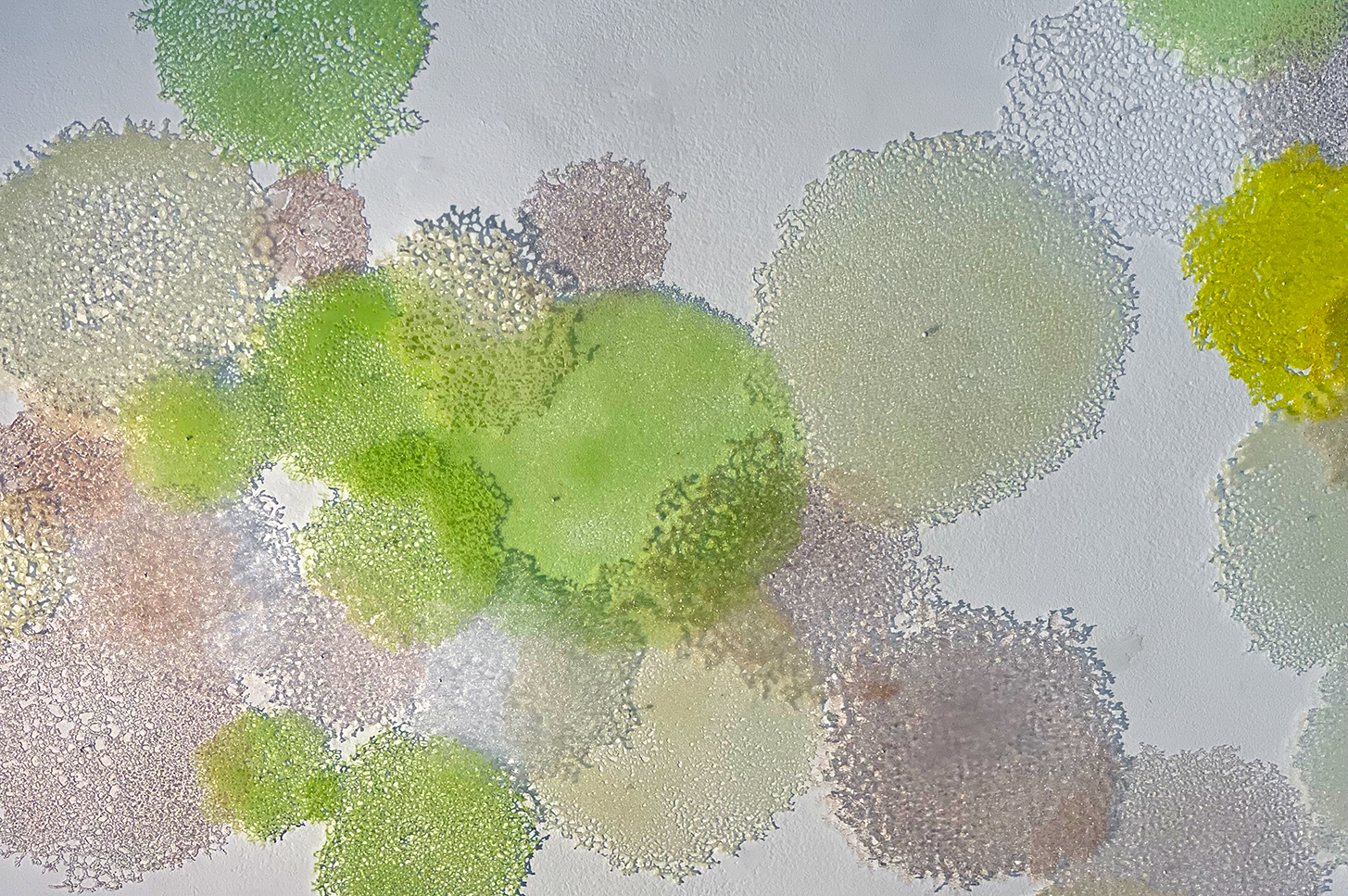

Hiromi Takizawa, Trail Gazing, 2019–2023

For Zaiden, the words we use to describe glass—reflective, transparent, clear—are ideas and values that are currently in debate. Susan Stinsmuehlen-Amend and Nao Yamamoto’s painterly interpretations of traditional stained glass windows explore the optics of glass as something we look through to perceive the world. Ethan Stern pushes beyond traditional forms in his exploration of color and texture, while his wife, Amanda McDonald Stern, crafts high-design vessels in her Modular Form Studies.

The Optics of Now reflects Palos Verdes Art Center’s ongoing commitment to the showcase of glass and its instruction as a studio art medium. While it is extraordinary for a small community like Palos Verdes to have three active glass studios, Brayton points to the grassroots support that made it possible.

“It really came from the community,” he shares. “It came with an idea, first of all, which everything does, but it was the people in the community helping out to get this thing going that made it happen.”

The Optics of Now: SoCal Glass is on view at Palos Verdes Art Center through April 13. For information and a list of participating artists visit pvartcenter.org.