A Local Photographer Ditches Digital and Celebrates the Imperfect with Her Work

Life through a lens.

- CategoryPeople

- Written byTanya Monaghan

The redwood trees lining the ocean of her childhood in Northern California and Oregon inspired Vania Francesca Zask to be a photographer. Family albums filled with people and wild natural beauty provided a deeper connection to loved ones after her parents divorced. Those photos made a huge impact on her life long before she made the decision to pursue photography as a passion and career.

After high school in NorCal, Vania returned to the South Bay (she was born in Hawthorne) and made a home for herself in El Segundo. She started with film, processing her photos in a darkroom. She loved the work, but photography took a back seat as she focused on being a young mother to her husband John’s two children and helping him run his plumbing business, JZ Plumbing.

As the kids grew older, Vania slowly got back into photo-graphy. She bought a digital camera this time—but soon discovered the thrill just wasn’t the same. Already enamored with the photographic process as much as the art, the digital process killed her interest the moment she inserted a memory card into the computer. Staring at thousands of images on a screen, she realized it wasn’t for her.

“I want to be outside. I want to be more tactile with my life in general. And I think everyone can relate to this sentiment at this point in time,” she says. “I want to be able to use my hands and do something I love, so I decided to go for it and started looking for old cameras. The digital era changed everything. These old, amazing cameras that were untouchable for me 20 years ago were now going for nothing.”

Her cameras are mechanical, run on batteries, and have no computer chips and no software. And she treats them like gold. “I have a fascination with holding this 100-year-old treasure in my hand, which probably hasn’t been touched in decades,” she shares. “Then I actually use it. I am determined to get them to work, and for the most part they do.”

When a guy at Sylvio’s Camera & Digital asked her why she shoots with film, she told him her reason: the click. “There is something about the click that is so wonderful.” Vania gave me a demonstration of the satisfying sound with her RB67—the first medium-format camera she ever shot with and the camera she recently used for photos with local clothing company Birdwell Britches.

“I have a fascination with holding this 100-year-old treasure in my hand, which probably hasn’t been touched in decades, and then I actually use it.”

She then picked up a Graflex Super D camera from the late ’30s. This sound had a long, vibrating roll ending in a slow click. For Vania, using film is like putting the needle on the record when playing vinyl. Although digital is far easier, what makes the film process special for her are the tactile nuances—like hearing the crackle when the needle hits the record before the sound flows.

Vania also loves the limitations of film photography, like having only 36 shots for each roll. For her it’s not just about the final product; it’s more about the experience, process and practicing restraint. There’s a ritual of putting the film in the camera, looking at the light and seeing things through the lens. “It helps me slow down, focus and really think about the shot instead of mindlessly taking 500 shots and hoping for the best.”

One of her favorite underwater cameras is a Nikon Nikonos III, designed by the late Jacques Cousteau. It is compact, fun and easy to use. Rather than backing down from the added challenge, Vania has gone to great lengths to shoot film in the water, including using a nonwaterproof camera such as her Pentax 645 from the ’90s. She saved up for a year to buy the camera housing from a guy who lives in Australia and has been making them for 40 years.

When Vania shoots in water, she usually sticks her camera inside her wetsuit tied to her back. She uses several waterproof cameras—even disposable ones. She also sometimes uses expired film, which adds to the excitement, never knowing if the film will cause a shift in color. In fact, sometimes nothing comes out at all.

Vania goes by @surfmartian on Instagram, a name inspired by her love of surfing and passion for documenting what she experiences from a different perspective. She is, of course, aware of the irony that her shots captured on film are showcased on the digital platform. But it’s not just about the image; it’s about the whole experience of capturing the image.

“Being present is hard. Finding a hobby or something I can fully focus my attention on has really helped me. It has helped document my experience of life in the South Bay.”

Along with the surf, Vania captures a variety of subjects, from details of old buildings in El Segundo to her favorite muse and sidekick: her 13-year-old daughter, Marley. She also creates a weekly podcast on film photography called All Through a Lens, highlighting other photographers who shoot with film.

Currently, her focus is on women and people of color, doing what she can to lift up those voices in her art. She also loves connecting with like-minded people of all ages: the older generation of film lovers who tend to only know film; the middle-aged generation wanting to reconnect with it; and the younger generation who are learning about it for the first time. When people want to learn about film photography, she will even send them some of her own cameras to get them started.

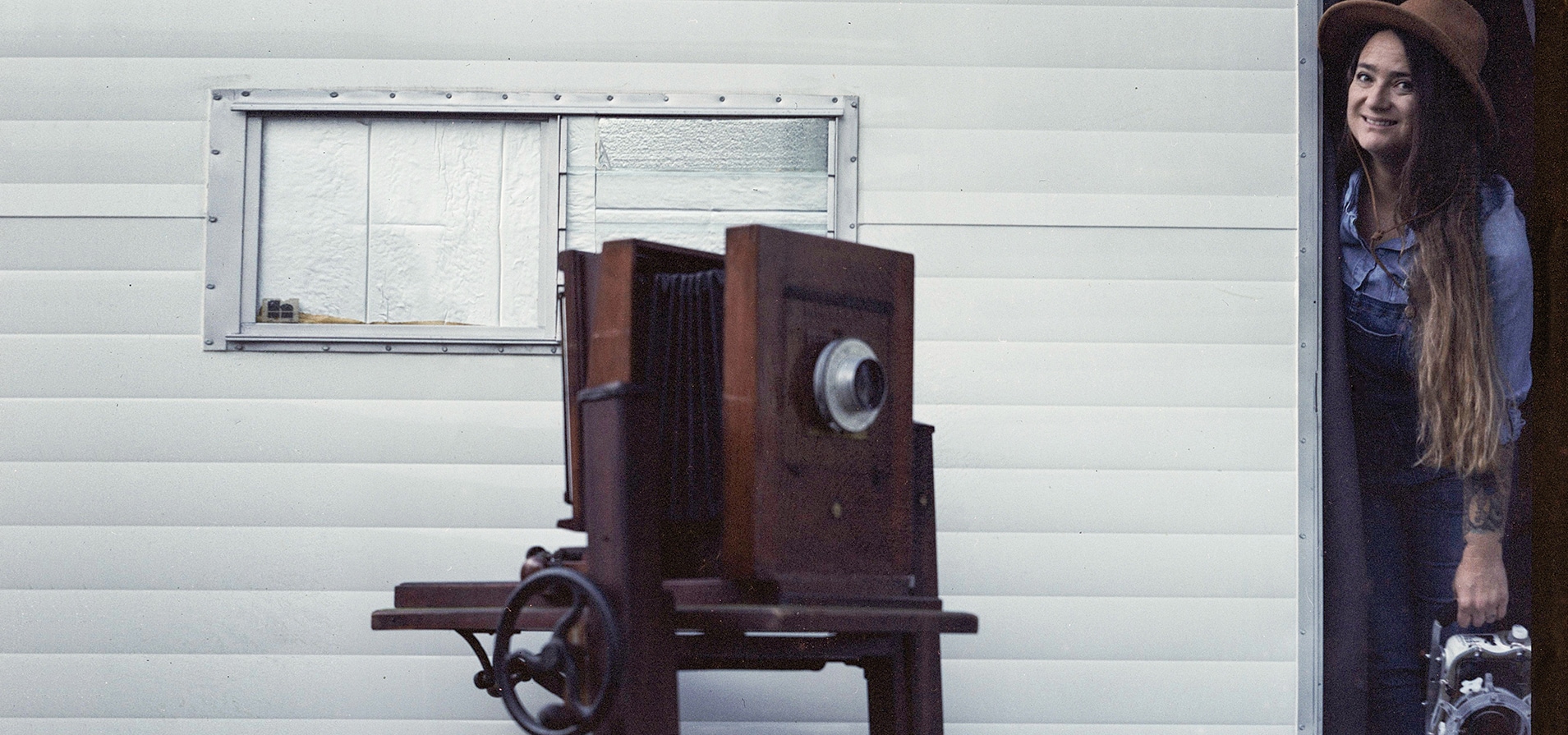

It was during the dark times of COVID-19 that Vania converted a refurbished trailer into a darkroom. Parked in her driveway with blacked-out windows, it became a source of light in her life. “There’s no working plumbing in it, so I have been using buckets to develop, process and print in there. I literally plug into my house to print my work,” she says. “This was the last piece that I needed to complete the full photography experience for me.”

From developing to processing, printing and scanning the film, she does it all by hand. In an age of retouching, she chooses to not change the colors or settings once she scans her images. She wants them “as is,” as authentic and raw as possible.

Vania’s next project is a book featuring generations of women surfers in the South Bay. She shot each of them with a Century Number Seven camera, dating back to 1905 and found in an antique market in Paris 30 years ago. Vania worked hard to get this huge, old beast functioning again.

“When you break it down, a camera is really just a light box with a hole in it, so I think it can work,” she says. “I got an old World War II lens, which I will mount on it. Then I’m going to take black-and-white close-up portraits of women with this 120-year-old camera. I am going to ask them questions about what it is like to surf in the South Bay as a woman.”

In stark contrast to the digital age of instant everything, it is the slow, deliberate care and love that Vania puts into the process behind the lens that brings out the richness and beauty of life in front of it.