About Face

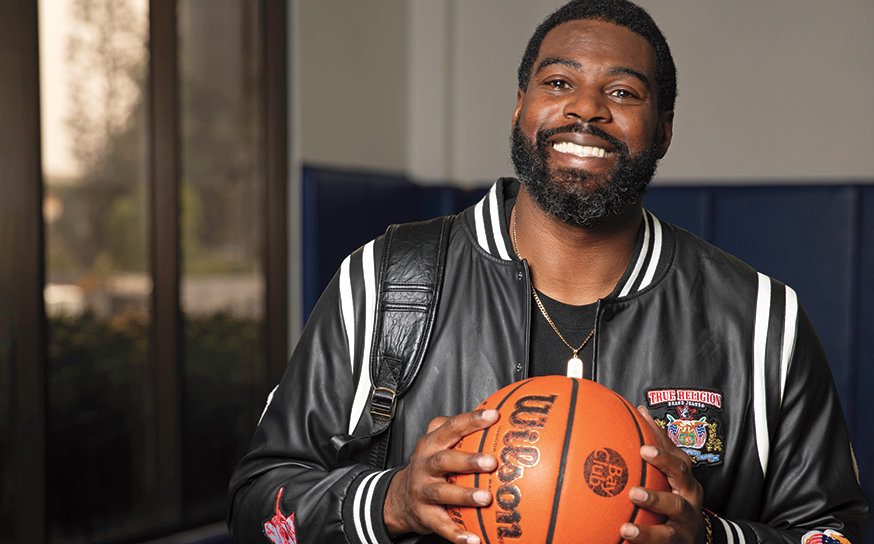

South Bay photographer Al Satterwhite sits for a young photographer, just starting his own career, and reveals a textured life as deep as the gaze of his famous subjects.

- CategoryPeople

- Written ByJack Zellweger

- Al Photographed byJack Zellweger

- All Images ©Al Satterwhite

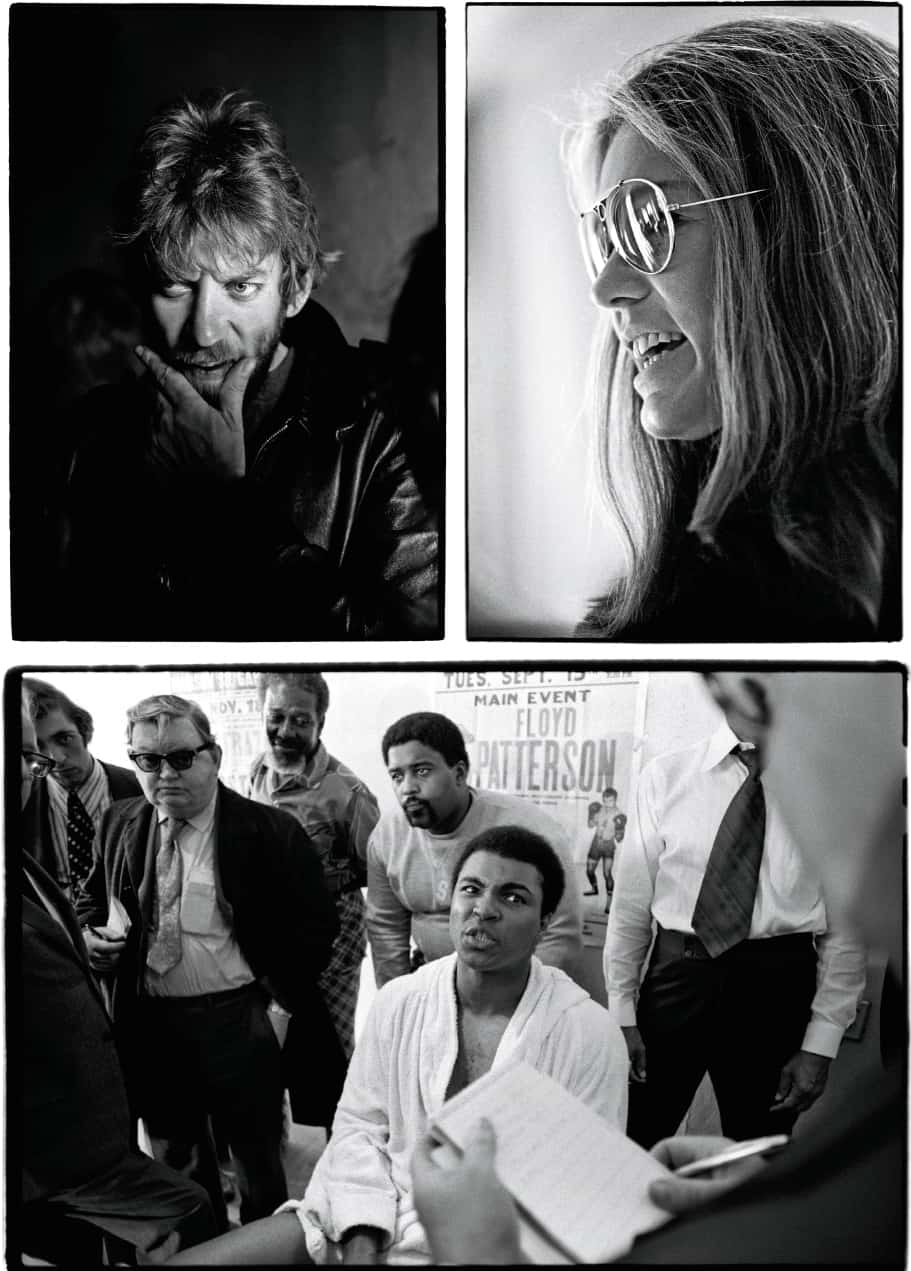

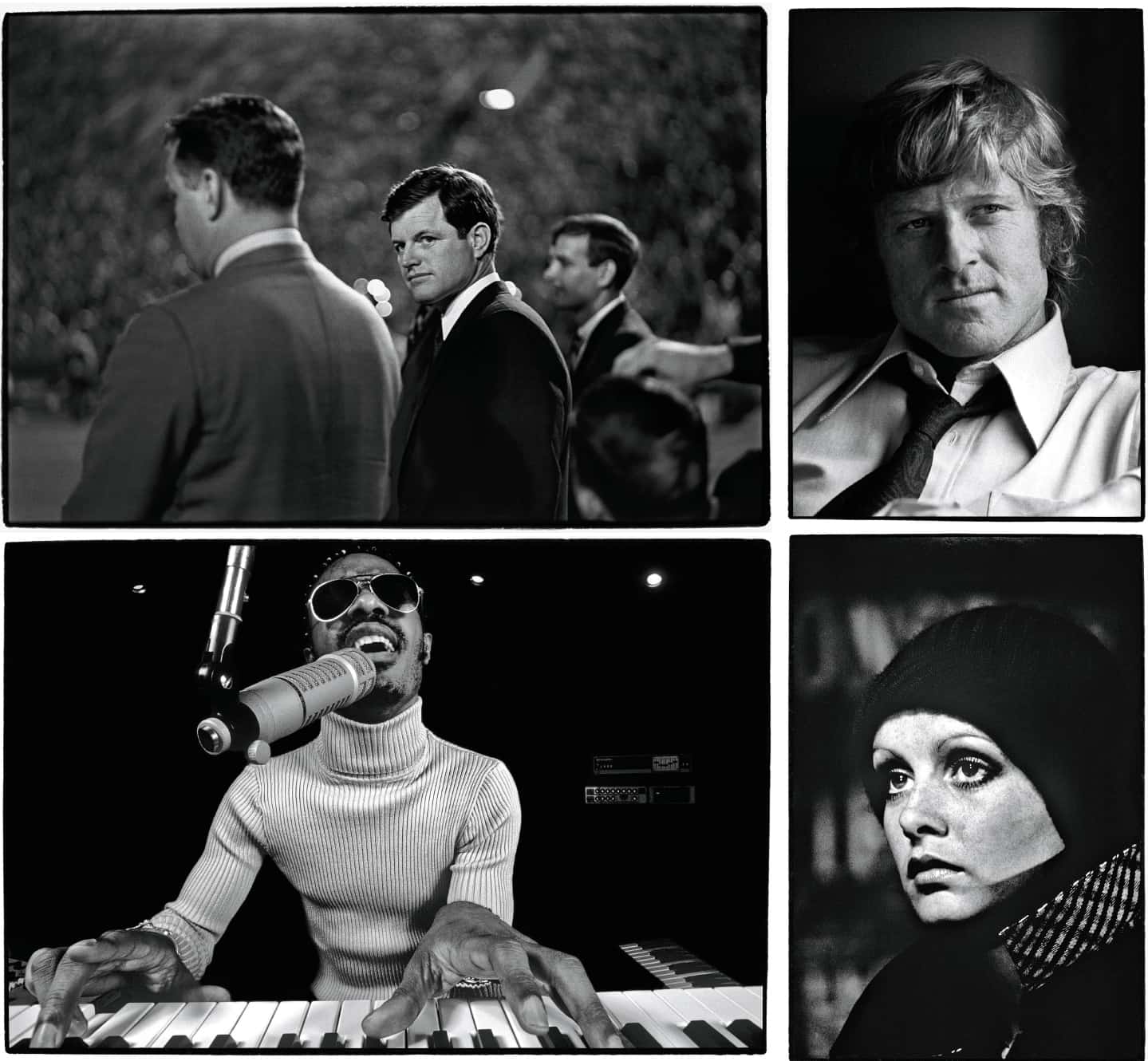

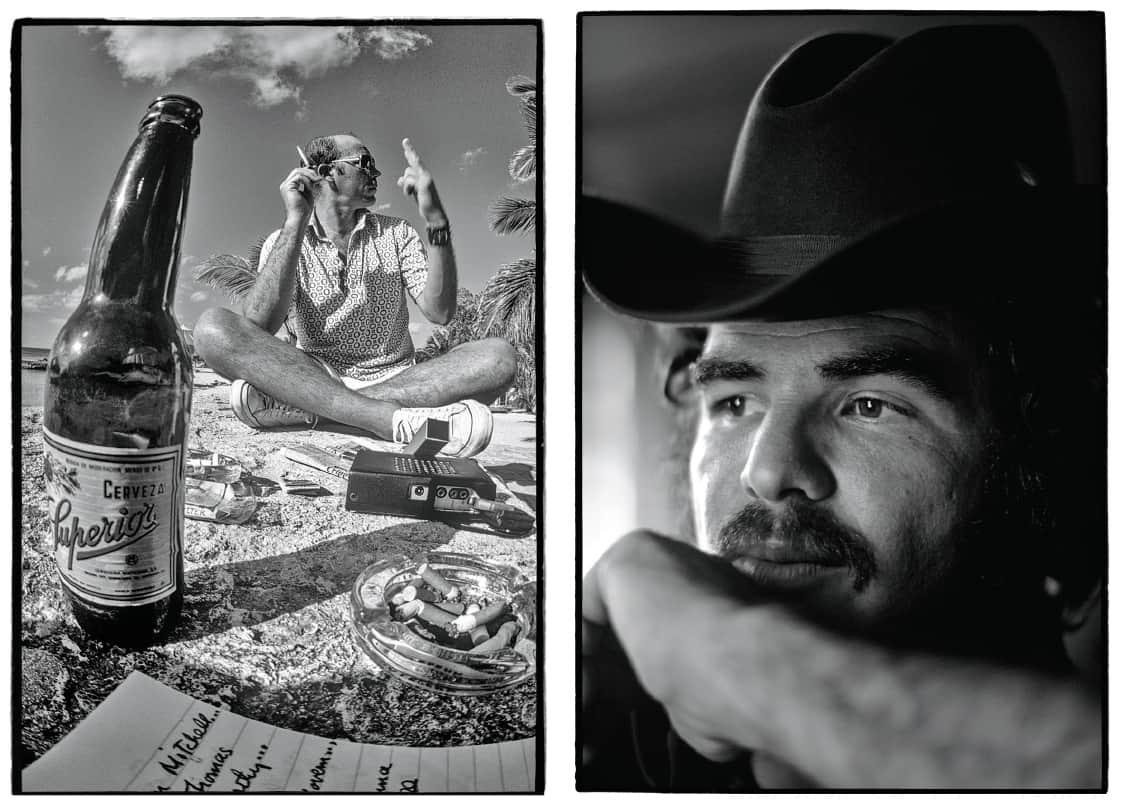

Through his environmental portraiture, South Bay photographer Al Satterwhite has immortalized some of the 20th century’s most fabled iconoclasts … Muhammad Ali, Jane Fonda, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Stevie Wonder and Hunter S. Thompson are just a few who have been in front of Al’s lens.

We flipped the narrative this time. Al Satterwhite is markedly uncomfortable in front of the camera.

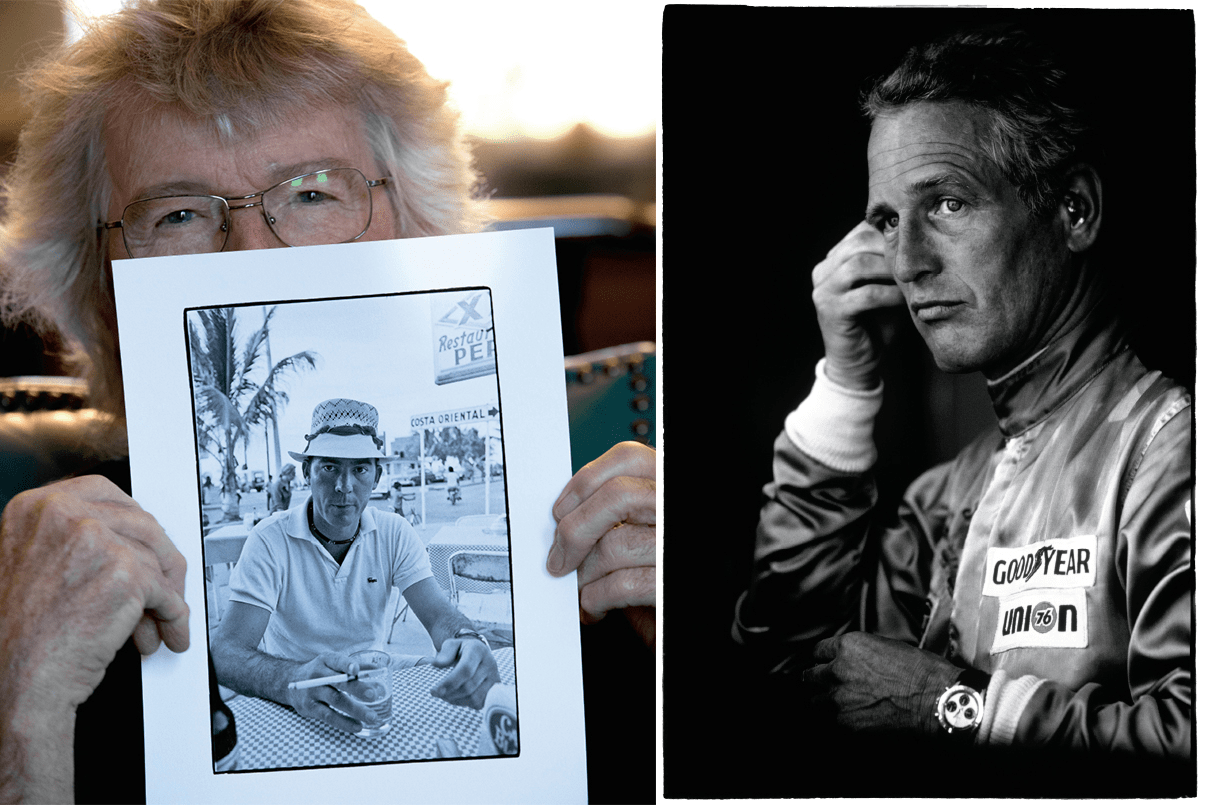

“I’m not used to this!” he remarks as I snap photos of him in his Torrance apartment. Al leads me through his career in photos on his home’s walls. Walking around the room is like walking through time. It’s an impressive body of work. How did he accumulate so many photographs?

Al’s career in photography blossomed, but it started with humble beginnings. Born in 1944 in Biloxi, Mississippi, he moved to St. Petersburg, Florida, at an early age. He found his passion in high school at his local paper’s student section, and by graduation it was more than a hobby. He had joined the staff of the local newspaper, the St. Petersburg Times.

Al then took his talent to college, where he started shooting at the University of Florida’s student paper. “I developed all my own photos in their darkroom,” he shares. “I had unlimited access there.”

But Al started college in a major he came to realize wasn’t for him: aerospace. “I was a terrible student,” he remarks as he recounts all the required science and mathematics classes. “I barely passed my freshman year.”

Eventually he switched his major—and even his college—from aerospace at the University of Florida to photojournalism at the University of Missouri. It was there Al built a darkroom in his apartment.

“You don’t need much for a darkroom,” he notes. “You just put black plastic sheets over the windows … and use your bathtub for the chemical trays.”

He worked hard on his craft and developed hundreds of black-and-white frames over the course of his time at school. After five years of college, Al ended up getting only a two-year AA degree. “I realized I had gotten as much of a college education that I was ever going to get,” he says. “You’re only as good as your last shot anyway!”

Al returned to St. Petersburg, shooting for his local paper, but wanted to get out of the newspaper business. He soon became the personal photographer of then-Florida Governor Claude Kirk Jr. “I spent the majority of my time in a Learjet traveling with the governor,” he says.

But after 13 months he quit to start the next chapter of his life. “I got bored of politics,” he adds, laughing.

After his experience with the governor, Al was hungry for exposure and had big dreams of getting photos in LIFE and Time. “You could make a name for yourself if you went to Vietnam,” he says. “You could get killed, but you could also make a name for yourself.”

Al continued to work for his local paper, joined a local army reserve unit and planned to join his best friend, Robert J. Ellison, chasing big dreams in Vietnam. The military didn’t see it his way. While Al stayed behind, Robert went on to photograph the war and make quite a name for himself, producing timeless images that were printed in national magazines.

Unfortunately, Robert didn’t live to see his photographs published. “He was the closest thing I ever had to a brother,” recalls Al. “We argued cats and dogs, but we were on the same wavelength and we both loved photography. It was the single worst day of my life, the day I got a call from AP that he had been killed. That kind of soured the whole deal on Vietnam.”

Sticking to photography, Al went on to have a successful freelance career, shooting for Fortune, LIFE, Travel + Leisure, Newsweek, Playboy, Sports Illustrated and People. Despite his success, Al says, “Freelance is hard. You’re always looking for work. You can never turn anything down. The first seven, eight, nine years of my life as a photographer, when I first started freelancing, I’d get one job a month, $150 to $200 per day. It’s not a lot of money!”

Despite the financial struggles early in his career, Al has no regrets about his trajectory. “I wouldn’t have been doing it if I didn’t love it,” he says. “I’ve gotten to travel and meet a lot of people in Europe, Australia, Africa, you name it. I’ve shot people whose religion involved handling snakes. One time I got onto the floor of the French stock exchange to take photos, just by talking. These are the skills you pick up—you could drop me in any country, and I could figure out how to get by, how to get a meal, how to get some money, and how to get where I need to be to get the job done.”

Al didn’t freelance forever though. He soon “got bored” again and started on yet another path in 1980—deciding that he needed to be in New York, where he established his own production company for advertising. He began shooting for big clients like Sony, American Express, DuPont, Nikon, Porsche, Polaroid, Saab and Universal Studios. “I struggled financially; then I started my own company,” he says. “It was a success.”

As we speak, two huge, colorful prints hang above Al in his living room. The prints, he explains, are by the late Pete Turner and Richard Avedon, two heavy influences—both masters of color and black-and-white whose pull you can feel in Al’s own work, especially in his advertising career. “You look at other people’s work, you look at magazines, you look at paintings. You don’t copy it, but you try to bring it forth when you need some inspiration. You just shoot, shoot, shoot, shoot, shoot, and soon enough you develop your own style basically subconsciously.”

Al recounts one of the most memorable and harrowing jobs from his advertising career: shooting oil rigs off the coast of Mexico. “After about an hour of shooting at dusk, we were flying out of an airfield that had no radio control and no lights. We were coming back in the dark with the art director, client and an account executive—running dangerously low on fuel, with too much weight. We were lucky to get back to the field with enough gas in our tanks. From then on I only let the art director go up with me—no one else.”

On another helicopter shoot in the Everglades, Al says, “All of a sudden, the pilot lost the hydraulic steering, so we headed back to base. When we were almost there, the engine cut out. Our helicopter turned into a rock, and we landed hard, sliding through the muck after we touched down. We had to be rescued by an airboat.”

Eventually Al’s willingness to do what nobody else would do earned him newfound financial success. Al got once-in-a-lifetime experiences on his shoots over and over again and spent most of his time on planes, traveling from client to client. “First they started paying me enough to fly to the West Coast … then I got to travel all over the world.”

He thinks of himself as kind of a nomad, a bit of a vagrant, a gypsy. He never had children or really settled down in one place. After several years of building a reputation in New York City, Al presented his knowledge of photography to the podium, making guest appearances all over the country. He lectured at Boston University, The Brooks Institute, as well as the well-known Kauai, Maine and Missouri workshops, just to name a few.

Al’s work also appears in several permanent collections. “It’s really nice to have a museum say that they like your work enough to want to keep it,” he says.

Museums hold Al’s most well-known portrait work, including his famous photos of Mario Andretti and Hunter S. Thompson at The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery and his portraits of Muhammad Ali at The Museum of Fine Arts Houston. Al’s work also appears in the permanent collections of several California museums including Santa Barbara Museum of Art and The Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

He has published several photography books, including Titans (iconic images of Muhammad Ali and Arnold Schwarzenegger), The Cozumel Diary (including original photographs of Hunter S. Thompson), The Racers (about the most prosperous age of car racing, 1962 to 1974), Carroll Shelby and Satterwhite on Color and Design.

Al recently completed a new photographic book entitled Southern Exposure, which includes never-before-seen images taken by him while he held the staff photographer position at the St. Petersburg Times newspaper. The book includes images of daily life in the south, with strong emphasis on how different life was 50 years ago.

As I finish my interview with Al, I reflect on the immense experience sitting in front of me. Al Satterwhite truly leads a life well lived and has made his mark on the photographic community. I take a final look at the frames all around the apartment. The images speak for themselves.