It’s 6 a.m. on a cold South Bay morning in February. The sun has yet to grace its warmth over the coastal rooflines facing seaward. I look at the thermostat from inside my well-heated car. It reads 47º outside and a toasty 80º inside. The ocean surface is calm with a light Santa Ana breeze coming off the desert, giving the ocean surface that sharp, crisp, textured appearance. Not a soul in sight. Something inside me exhales. Ah yes … this is why I live here.

I tightly grip my coffee as I look out over the ocean—trying to get enough caffeine down the gullet to ward off the icy breeze that will undoubtedly cut through the artificial warmth I’ve created inside my car as soon as I open the door. Just as I’m about to pull the door handle to exit the car, the second-guessing begins. Well, the surf isn’t that good out there. Or, the tide is dropping, it’ll be junk within an hour. Not worth it. Every surfer knows the voices that try to keep you in your car.

Just then a man walks right in front of my hood. Through the windshield he looks to be a 70-something-year-old, bare-chested man wearing nothing except a pair of elastic-waist swim trunks and a pair of flip-flops. I look back up at the thermostat. Yep, still 47º. And that water is no more than 54º.

Here I am, huddled in my car—which is now more of an incubator than a means of transportation—clutching a hot coffee, staring at the thermostat, using my best Jedi mind tricks to see if I can move the outside temp up a couple degrees. Yet I watch this older gentleman in nothing but a pair of shorts saunter his way down to the beach.

“I can’t explain it much more than it is just something I enjoy and have a passion for. I love getting in the water. Any reason why someone wouldn’t want to do this simply does not compute with me.”

His walk is not hurried, nor is there a determined, must-persevere posture about him. None of that. Just a nice, easy stroll before the sun hits the coast to go meet the day at the water’s edge. He makes his way to the closed lifeguard tower and places his sandals on the rear deck. Then with one hand he clutches a pair of swim fins and in the other a pair of goggles. That’s it.

As he approaches the water’s edge, he suddenly stops. He stares out over the horizon. A moment. A pause. Maybe a prayer, maybe a memory. The cold breeze blows across his back, and by now the early-morning dog walkers overdressed in their Eskimo jackets have stopped to watch.

Then he begins to move into the shallows. When he gets about waist deep, he pulls his legs out from underneath his body and fully submerges himself in the frigid waters. As he resurfaces, I could hear from inside my incubator a shriek. Not of shock, alarm or distress. No. This was a shriek that uses the same vocal cords as a child opening a present at Christmas. It was the sound of joy. Exuberance. A sound that didn’t care who heard nor who was watching because it comes from a place of overflow. That’s what I heard.

And then he started splashing. I watched in dismay. It looked light. Playful. It was carefree, like watching the bear at the zoo play in his pool on a hot summer day. And yet the backdrop for this behavior was something quite ominous. Cold. Uninviting. Wild.

Finally, he launched a couple fistfuls of ocean water up into the morning sky and before they could drop, he began to head out to sea with the same pace as his stroll down to the water. Slow, graceful, metronome-like repetition. Arm over arm, swimming off into the salty, cold distance.

This is Dick Freeman. I have had the great privilege of watching Dick’s morning routine for more than 20 years now. Rain, shine, wind, waves, it does not matter. Dick has had the same daily ritual of getting in the ocean and swimming the same 1-mile course five days a week since 1999.

But why no wetsuit? Is he a part of some cutting-edge trend in modern-day health and wellness? Guess again. The only reason he doesn’t use a wetsuit is simply that he couldn’t afford one when he first started swimming. So why use one now?

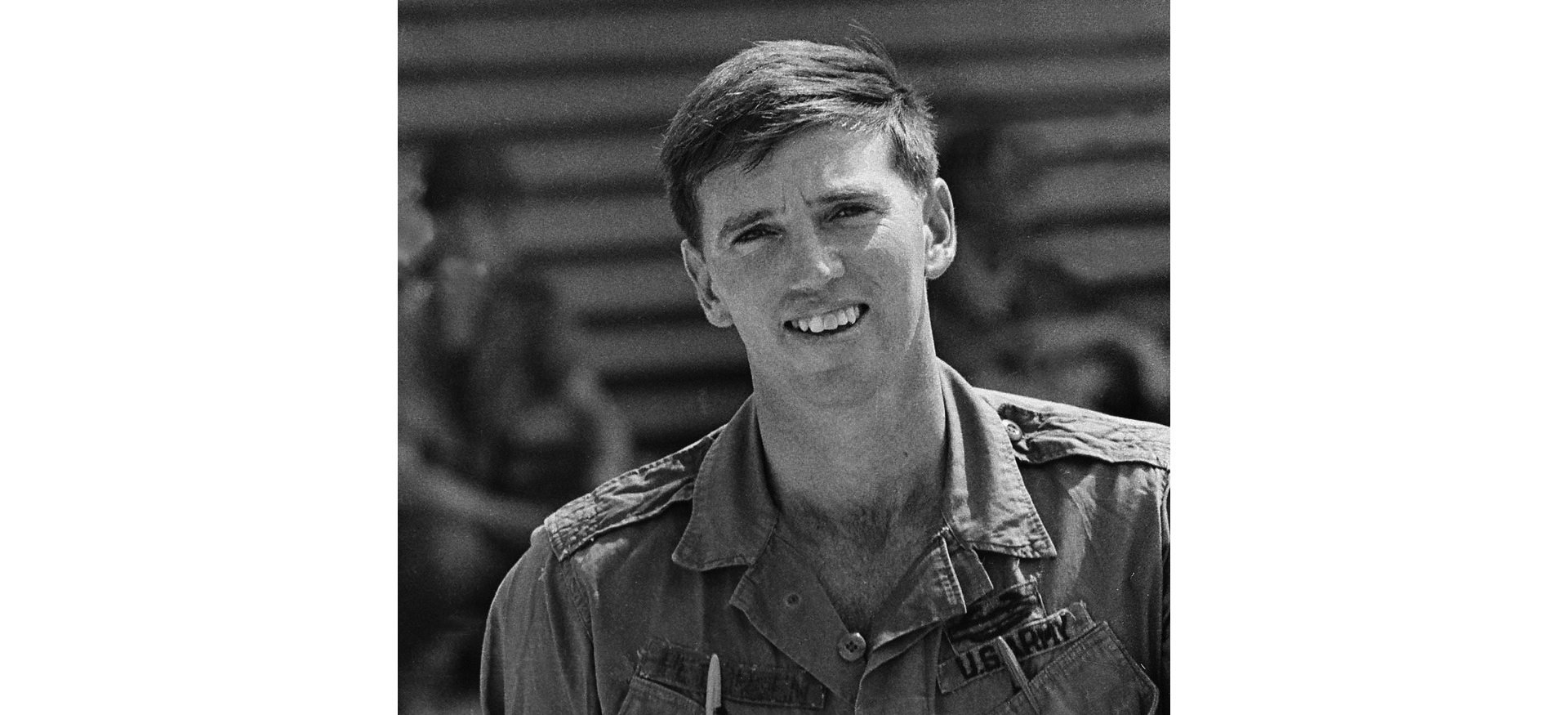

Dick was born in Hawthorne, grew up in Lawndale, and was on the water and swim teams at Leuzinger High School in 1954. Too wiry for football, self-proclaimed lousy at tennis and even worse at golf, swimming seemed to be the best natural fit. After high school he became an ocean lifeguard for about 10 years before getting drafted in 1966 and heading to Vietnam.

In Vietnam Dick was a part of the 49th Infantry Platoon Scout Dog. Each soldier paired with a dog whose job was to sniff out mines, booby traps and ambushes. A task not for the faint of heart, yet his platoon was the best. The most effective. And also suffered the highest number of casualties.

One rainy night, alone in the rice patties, Dick looked up to the heavens asking to go home. He’d seen enough. Been through enough and was now pleading for mercy. Spare him. Take him out of where he has found himself. The next few days the sun came out, the dust settled, angst lowered … until an explosion. A piece of shrapnel went flying through the air straight through Dick’s foot. That was it. He spent two months in the hospital and was discharged from the infantry and later came home on March 15, 1968.

Post-Vietnam, Dick pursued a career in insurance. Building a career for himself was his central focus. He succeeded. Then one evening, climbing a flight of stairs, he found himself winded by the time he reached the top. That did not sit well with the former lifeguard and Vietnam vet.

So he reverted to his childhood activity: swimming. That was in 1999. From that day forward, Dick has spent every week in the ocean swimming. Five days a week (5,720 days and counting), at the same time and the same course each day.

In 1999 swimming came back into his life. He took it back up for the same reason we all get off the couch, lose weight, build fitness, wear those jeans again.

But something happened.

When you spend five days a week in the ocean rain or shine, something begins to shift. The goal is no longer to fit into those jeans. That obviously happens, but something else begins to happen. A new driving force. It begins to root itself to something very deep—something so primal it becomes difficult to put a finger on.

When I was interviewing Dick for this story, I kept wanting to understand the root of “why.” Why do you get in the ocean and swim five days a week? Why do you not care if it’s cold? Why do you swim the same 1-mile course every time? Why, why, why? We want to rationalize what we do not understand.

I was anticipating an answer that dug into the horrors of Vietnam. I was anticipating some “aha” wisdom to be imparted on me like a shining light from above. I was anticipating dramatics. I tried so many different angles to best understand the “why”—to the point that Dick was finally forced to answer what was now a very poignant question. WHY?

With nowhere to go, he just looked at me with such kindness, with patience in his eyes as my younger, white-knuckled effort tried to rationalize what I could not understand. He was so gracious. He looked me right in the eye, smiled, then said, “Jared, I can’t explain it much more than it is just something I enjoy and have a passion for. I love getting in the water. Any reason why someone wouldn’t want to do this simply does not compute with me.”

Mic drop.

Some of the biggest, most awe-inspiring things this world has to offer do not give us the luxury of understanding them in their entirety. Explain love. Explain forgiveness. Explain dancing. Explain eating nachos at Dodger Stadium on a warm Chavez Ravine evening. Save yourself the effort in doing so, because you’ll just sound ridiculous when you do.

Instead create a category of awe and wonder and implode any linear, logical definition. In Dick’s case, the simple act of returning to the water’s edge day in and day out is where the connection takes place that dictates how everything else will go—and not the other way around.

And in a world that places so much value on a feverish attempt to make sense of every single thing, it’s nice to have people like Dick who can show us where some of the treasure is buried. Because sometimes it is in places like 54º water at dawn without explanation.